For my articles about last year’s Bread & Puppet Vermont experience, go here and here and here.

August 5, 2007

Spectacle for the Heart and Soul

GLOVER, Vt.

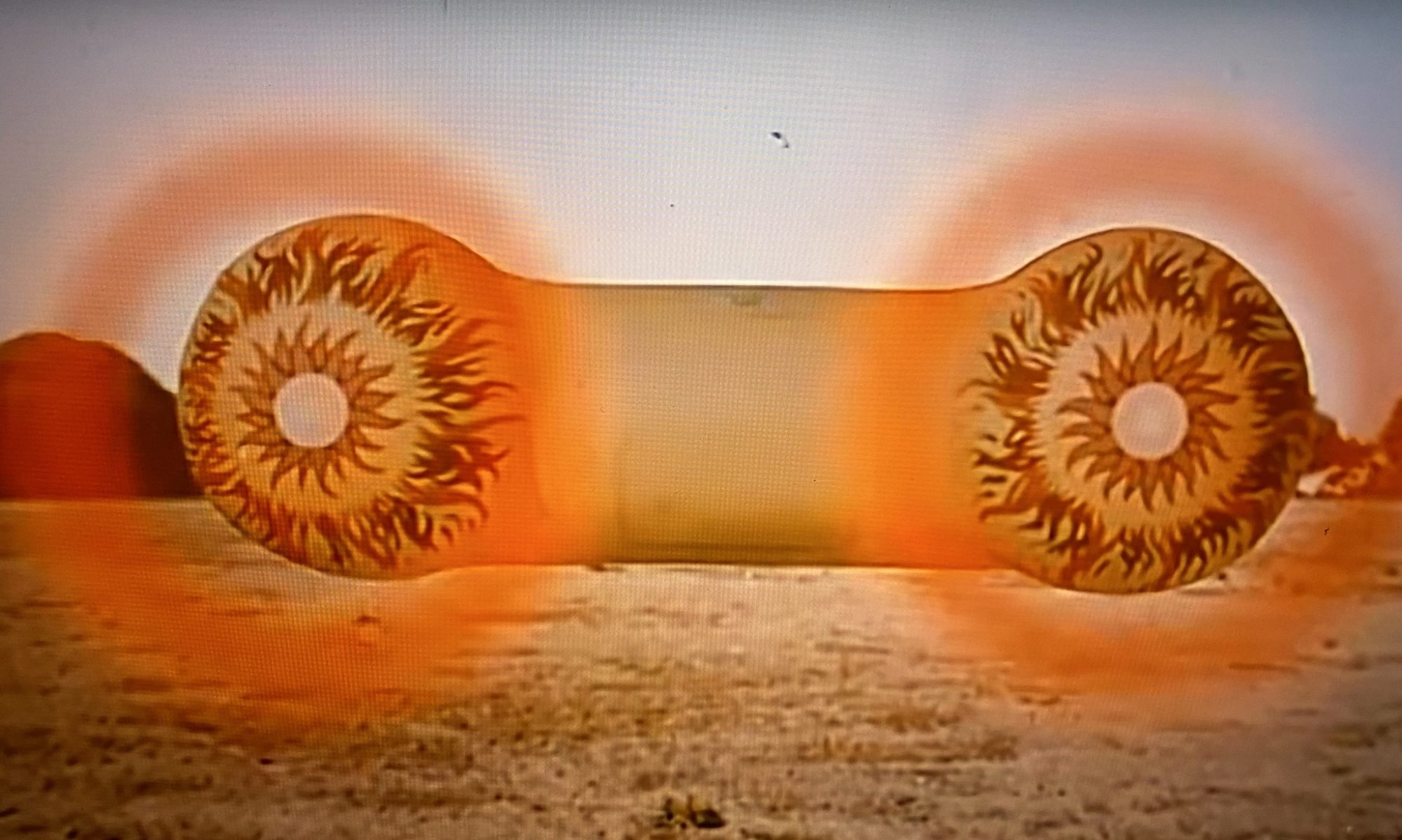

FOR the first time in many summers the Bread and Puppet Theater will travel nine hours from northern Vermont for a New York City gig, at Lincoln Center on Wednesday evening. Then the troupe will turn around and ride back to its farm just below the Canadian border, where it will put on the same show. You can easily spot the group en route: 1963 school bus, painted sky blue, with a mountain landscape, an angel and a beaming sun on the side.

People who know of the troupe without really knowing its work tend to link it to political street theater of the 1960s, an accurate but incomplete association. Recently I’ve been thinking of the theater in a contemporary context. At a time when the art industry is awash in cash and privilege, and theater tickets routinely go for $100 or more, Bread and Puppet continues, more than 40 years on, to live an ideal of art as collective enterprise, a free or low-cost alternative voice outside the profit system.

I have another association with the troupe: Bread and Puppet gave me the single most beautiful sight I’ve ever seen in a theater. That was in 1982, in the sloping, wide-open field that is part of the theater’s farm in Glover, Vt. There the collective was presenting a two-day festival, Our Domestic Resurrection Circus, as it had done almost every summer since relocating from the Lower East Side of Manhattan in the early 1970s.

The circus, a bunch of political skits, concerts and vaudeville acts, took place in the afternoon, and it was fun. (The troupe’s Lincoln Center appearance will follow more or less this format, on a smaller scale.) Then at sunset came the pageant, a kind of morality play told in epic visual terms. During Vietnam the themes had been specific. Wrongs had a name and a solution: Stop the war. By the 1980s the issues had become many and complicated — threatened nature, global consumerism, nuclear dangers — and remedies far less sure. The 1982 pageant had an odd tone, brusque and apocalyptic. It opened with a bucolic scene: little cutout houses and trees carried onto the field, followed by puppets of dancing cows. Villagers in masks arrived, milked the cows, settled down to bed, woke up, had children who within minutes had children of their own. This was ordinary life set to haunting music: vigorous, low-church American folk hymns from the 19th-century collection “The Sacred Harp.â€

Suddenly four dark puppet horses with devil riders wheeled in from afar, backed by a huge dragon. Almost without warning the devils waved black banners over the villagers, who fell to the ground, dead. The devils then piled the houses and horses together and set them alight. Good and evil alike were in flames. Moral chaos. End of story.

But not quite. As the fire burned, a half-dozen great white gulls or cranes — muslin kites carried on sticks by runners — soared up from the horizon and started flying in our direction. They came right to the flames and soared over them as if looking for signs of life. Then they circled back across the field, melting into darkness. It was fantastic. Only when they were out of sight did I see that night had fallen and stars were out. It felt like an impossible trick of stagecraft, a miracle. I had been simultaneously transported and pulled back to earth.

Last month, on a cool, rainy midweek day, I was back in that field, standing on the same hill, looking at the same horizon. Nothing had changed, but there is no pageant this summer. There hasn’t been since 1998, when a man at the festival was killed during an alcohol-fueled fight. By that time the two-day event had become a mini-Woodstock, attracting some 30,000 people who camped out in the surrounding countryside, overwhelming the resources of the theater and surrounding towns.

The result was that Bread and Puppet declared Our Domestic Resurrection Circus over. For good.

The theater itself, however, is still in residence on the farm and very much in business. It maintains an extraordinary archival museum of puppets and masks in a 19th-century barn — open every day, admission free — and produces hand-colored posters, banners and books, a main source of Bread and Puppet income.

If anything, the troupe is performing more than ever. It tours regularly, often to colleges, which pay to have Bread and Puppet entertain and inspire students. And the troupe presents free circuses and pageants at the farm, on a small scale, to audiences of 100 to 200 people on summer weekends.

Traditionally the troupe has consisted of a handful of resident performers; as of July there were four paid by the month and a business manager paid by the hour. And the group has always depended heavily on volunteers, either performers familiar with the troupe’s work or people trained more or less on the spot. This is still true. This summer the company includes a dozen or so resident interns who live in the original farmhouse or in nearby tents, sharing a communal kitchen, outhouses and a single house phone. (Glover is in a no-cellphone zone.) Most have art backgrounds, though that is not a requirement. A few are art activists. Several of them will be coming to New York.

New York City is where Bread and Puppet started. And when I say Bread and Puppet, I am primarily speaking of Peter Schumann, who founded the theater and continues to shape it. He was born in Silesia, now part of Poland, in 1934, the son of a Lutheran schoolmaster. During World War II the family fled to northern Germany, where, as refugees, they lived on scraps gleaned from local farms. The bread that Mr. Schumann bakes daily for the theater artists and for distribution to audiences after performances is made from the same kind of coarse, hand-ground rye his mother used at that time.

As a child Mr. Schumann learned to make masks and puppets at home; as a young adult he became interested in sculpture and dance. In 1959 he formed an itinerant dance group in Germany. He had also married an American, Elka Leigh Scott, and started a family, eventually having five children. In 1961 they moved to the United States, living first in Connecticut, then settling on the Lower East Side.

It was an exciting moment. The city was electric with new music, dance, art and theater, which combined in the work of people like John Cage and Merce Cunningham and in the Happenings organized by Allan Kaprow, Claes Oldenburg and others.

These artists inspired Mr. Schumann and helped clarify what he wanted to do: create a collaborative theater open to untrained participants. Performing and teaching would have equal importance, and the ideal audience would be neighbors, passers-by, strangers. The theater would have the gravity of ritual, the raucous humor of carnival and eyes and ears tuned to the news of the day.

In 1962 he created his first masked dance, and in the same year he took up puppetry again. He founded Bread and Puppet Theater in 1963. Mr. Schumann’s politics were communitarian and pacifist, and some of the troupe’s first performances were street parades, using puppets and masks to support rent strikes in economically vulnerable communities. For marches against the Vietnam War he made wearable, life-size puppets, the heads created from clay molds he made himself. Now artifacts of the theater’s history, they are his most striking and durable visual creations.

And the only place to get a sense of their imaginative range is in the museum at the Vermont farm.

When I first visited on the festival weekend in 1982, Bread and Puppet occupied one floor of the barn; now it is on two, and it is doubly astounding. Last month, with the Schumanns and the interns busy, I had the place to myself.

The barn’s ground floor is divided into three parallel corridors, once lined with stalls but now divided into alcoves holding figures and props from hundreds of past performances. The objects are vivid, but made of cheap materials and worn from use. Mr. Schumann calls the barn the museum for the Art of Impermanence.

Yet it is hard to imagine a more quickening sight than the installation on the barn’s high-ceilinged upper floor. All of Mr. Schumann’s largest puppets are here: immense pageant gods, madonnas and angels; giant butchers and salesmen; washerwomen in kerchiefs and skirts; Yama, the King of Hell, sprouting heads like cancers. Visually it is a coup de théâtre; conceptually it is intricate moral and narrative cosmology. If any single work could effectively fill the atrium space at the Museum of Modern Art, this ensemble could, and should.

For a brief time, in late spring of 1982, the barn was practically empty. That was the year that Bread and Puppet led the nuclear freeze parade in New York City during United Nations sessions on disarmament. Mr. Schumann brought some 250 masks and puppets from Vermont, rounded up and trained thousands of volunteers, and in just a few days organized one of the most spectacular pieces of public theater the city has ever seen.

Titled “The Fight Against the End of the World,†it was an epic in three stages that included figures with stars for heads, crimson-and-black imps swarming around a figure of death on a skeletal horse, and a tableau of white birds and a blue ark in full sail. In the midst of it Mr. Schumann himself appeared in a red-white-and-blue Uncle Sam outfit, perched atop sky-high stilts, dancing to a ragtime tune.

Hundreds of thousands of people lined Fifth Avenue, rapt, quietly beaming; many wiped their eyes. They had been given a gift, an image of affirmation on a tremendous scale.

But as was true of the Glover pageant later that summer, affirmation in Mr. Schumann’s work is always provisional, shadowed by the darkness that proceeds it. This has seemed more true over the years, perhaps as he has seen new generations of Americans retreat from an awareness of political urgency. Working in unreceptive times has made Bread and Puppet’s art tough even when sweet; emotionally severe even at its most beautiful.

For me the real affirmation of the disarmament pageant lay less in the fact that Mr. Schumann came to New York and created this hugely ambitious collective work of art than in the fact that immediately afterward he returned to Vermont, to a farm, to a barn, to the outdoor baking oven, to his workshops and to his own work, which has come to include an increasing amount of painting, most of which stays out of the art world’s sight.

And although he is personally a star — the theater historian Stefan Brecht calls him, with cause, one of the great artists of the 20th century — Mr. Schumann has kept faith with the redemptive politics of the everyday, of shared ordinariness.

I thought of this near the end of my stay at the farm last month. The theater does a lot of community outreach. That evening it was scheduled to give one-night workshops for around 50 Vermont high school students. They were all seniors in the Upward Bound program, established by President Lyndon B. Johnson in the 1960s to support students who would be the first members of their families to attend college.

In the past, I was told, some students took the visit as a night off, a chance to hang out and horse around. So I wasn’t expecting much when the vans arrived and the kids split into groups, one going to the print shop, another to a stilt-walking session, another to the farmhouse for a sing, with all the groups rotating, so each student was able to be in every session.

I wandered back to the barn, upstairs to where a puppet called Angel of the Earth stands, two stories tall and impassively protective, over the more than 40 years of Bread and Puppet history: one of the great sights of American art. I heard a ragtime tune outside; that would be Mr. Schumann teaching the kids to strut and dance on stilts. Then I heard the most beautiful music on earth. Choral singing.

I followed it, out of the barn, into the farmhouse and upstairs, to where Elka Schumann had just finished one singing workshop and was introducing a fresh batch of students to a “Sacred Harp†hymn.

The original melody came from England to America in the 18th century, she said. Then, as Americans developed a taste for more elite and refined culture, these hymns, written in a four-note style that anyone could learn, sounded rough and crude. So they passed from city to country, from the north to the south, where they became a pretext for community sings. Let’s try one, she said. The students shifted in their seats but sang the words with her:

And every man neath his vine and fig tree

Shall live in peace and unafraid.

And into ploughshares beat their swords.

Nations shall have war no more.

Then they sang them again, more confidently. By the third time they sounded like angels.Â