S.F. NEIGHBORHOODS Graffiti marring much of city’s street art – vandalism on the rise

Matthai Kuruvila

Published 4:54 pm, Thursday, December 27, 2012

Read more: http://www.sfgate.com/crime/article/SF-murals-become-targets-for-vandals-4150191.php#ixzz2GeFBUSjw

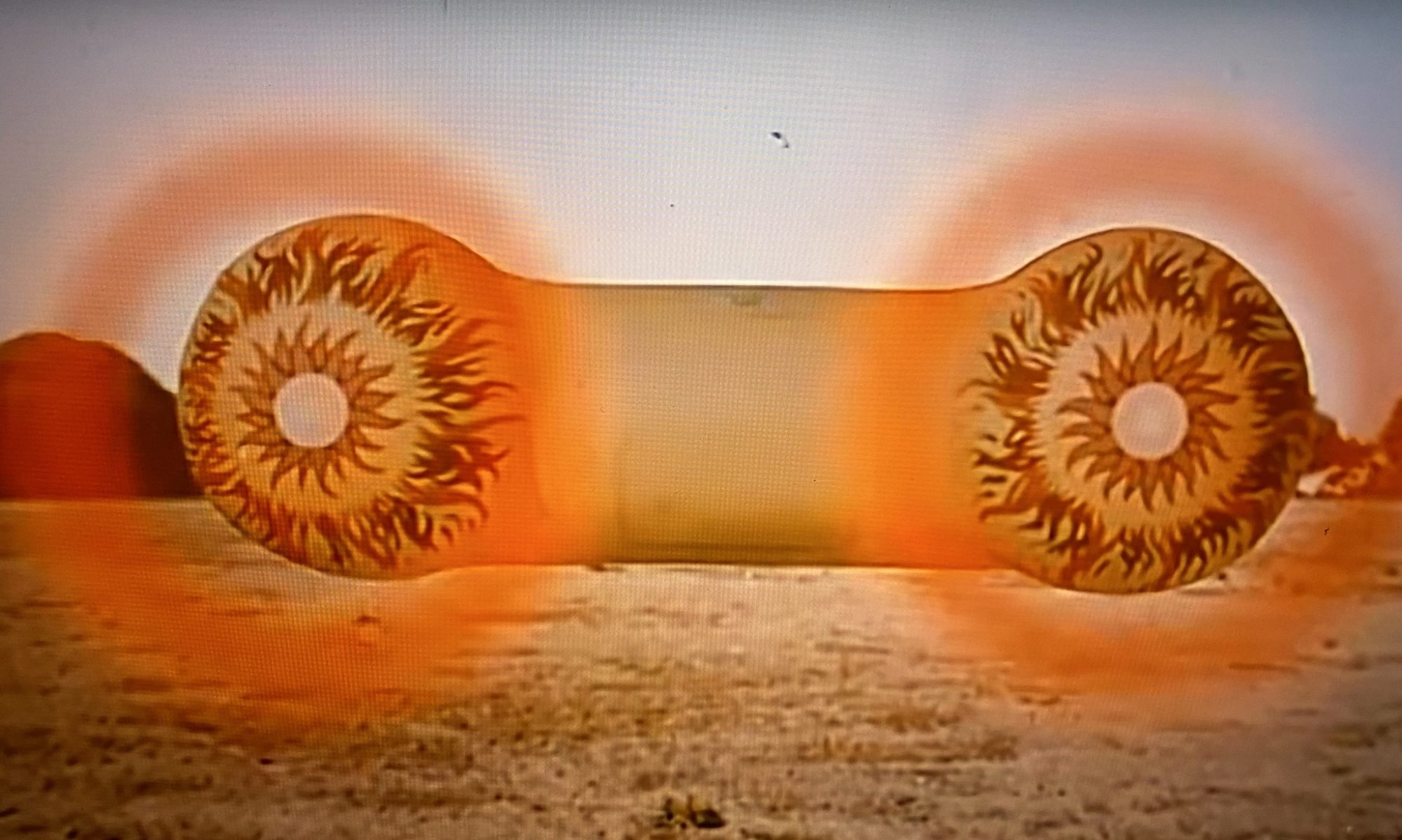

Muralists around San Francisco say that they’ve seen an increase in vandalism of murals by taggers, who are defacing the art with their monikers.

Vandals have wrecked murals from North Beach to the Tenderloin. In the city’s liveliest mural zone, the Mission District, muralists say it’s been particularly bad. Street paintings made in months have been ravaged in seconds.

“There’s been a very specific mural destruction going on,” said Russell Howze, a muralist and author who does street art tours of the Mission District. “There’s really no logic. I don’t know if there’s any organization or conspiracy behind it. More than anything, these murals are well-loved and huge amounts of time have gone into them.”

Vandals this year have defaced parts of the Mission District’s Clarion Alley, a 20-year-old street museum of murals. “Gold Mountain,” a North Beach mural depicting Chinese history, had to be repainted when the building owners couldn’t keep it free of graffiti.

While some view graffiti as an art form, taught in classes at schools and even sponsored by government agencies, unwelcome graffiti is a crime, punishable by jail and fines.

The Department of Public Works, which keeps track of graffiti abatement, received more than 21,800 requests this year for graffiti cleanup in San Francisco. It’s not clear how many of those calls, if any, were related to murals.

Expensive restoration

For the muralists whose works have been affected by vandalism, restoration can be expensive, time-consuming and sometimes not worth the trouble because the work just gets vandalized again.

Sirron Norris, a professional muralist, had his six Mission District murals defaced this summer. He spent dozens of hours fixing them, but one was beyond repair.

“I had to let it go to the wild,” said Norris, who prefers indoor murals as a result. “Tagging is so pervasive now.”

Public Works spends about $3.5 million a year on graffiti abatement. The majority of time and money is spent on removing graffiti – 90 percent of which are dealt with in 48 hours of a request, said Rachel Gordon, a department spokeswoman.

The city also does outreach, including classes in schools about graffiti. They teach people not to vandalize and how to do graffiti art responsibly and with permission.

In addition, for habitual victims of taggers, the city has a program called StreetSmARTS. The program awards up to $1,500 for artists to create murals on problematic walls to discourage unwelcome graffiti. Property owners pay on a sliding scale.

Over the three years of the program, there have been 50 murals created, said Tyra Fennell, director of the StreetSmARTS program. At least five have been defaced by graffiti.

One was completely destroyed, but because it was up for two years, Fennell said, “we consider that a victory.”

The city’s use of murals to discourage graffiti is not so different from what many corporations now do, including Walgreens in the Mission District, which has large murals on its walls.

Jet Martinez, an Oakland resident who has been one of the directors of the Clarion Alley Mural Project, which has been tagged repeatedly this year, called 2012 the worst year for tagging of his murals since he started in 1997.

He said he wonders whether the corporate and city use of murals has prompted the tagging by vandals who view themselves as subversive.

“I guess I can see how, in a misguided way, if you were a starting artist, to see somebody doing a legal piece, it might feel like ‘The Man,’ ” he said.

It’s a view Martinez says doesn’t jibe with history, nor today’s reality.

”

I personally feel like there’s room for everything,” he said. “It’s a big old city with tons of walls.”

Dealing with taggers

How muralists can deal with the tagging is another issue.

”

I struggle with it,” Martinez said. “When it happens to me, I want to go crazy, find everybody who is tagging and break their fingers.”

Susan Cervantes is known as the dean of San Francisco’s murals. She founded and directs Precita Eyes, a Mission District nonprofit that has created 500 murals over the past 35 years.

From her building on 24th Street, she can see a badly defaced mural across the street. She said Precita’s murals, one of which wraps around a four-story building, have largely avoided the defacing. She believes Precita’s history and community role may have protected its murals.

Cervantes, like others interviewed, says part of the power of street art is its vulnerability: it’s exposed to the community.

“That’s the risk that you take,” she said. “We don’t do it to deter vandalism, but we do it to make art accessible to people. This is what we started out as muralists to do.”

Matthai Kuruvila is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. E-mail: mkuruvila@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @matthai

Read more: http://www.sfgate.com/crime/article/SF-murals-become-targets-for-vandals-4150191.php#ixzz2GeF2kVtL