The early-20th-century advent of the automobile brought about many changes to society and how humans organized themselves. In a time when inventions revolutionized the way we communicated, travelled, and entertained, the auto created a powerful framework of the era. Over 100 years later, it still creates that firm, romantic symbol of freedom, uniqueness, and materialism that developing nations like China are quickly becoming aware of.

This modern, Fordist symbol has reached icon status among the American population. The automobile stands as a model of the first step to that hazy, idealized concept of the “american dream.” Put that money down, get that bank loan, and drive away with one of the most expensive things you’ll ever buy. A house with a family will soon follow, complete with (a 30-year mortgage) a pool, a grill, and a lawnmower.

This blog entry will use personal anecdotes to show the power of the car as an icon, and then show how this concept is currently being revolutionized by my current employer, Business Leaders for Sensible Priorities (BLSP). For a week now, I have thought about my own personal relationship with the automobile, and am surprised to see the obvious arc that propelled me to the job as CarnyMobile Operator. Today, at a Hot Rod convention in Gilford, NH, the loose strands came together, making me realize that changing American’s concept of their rides is serious business. I could be a catalyst for this change, or at least the current well-planned attempt.

Growing up in rural South Carolina, where neighbors tricked out cars and friends took it further, I can’t help connecting my past to my present. With the advent of online media, Burningman, the Alt Fuels movement, and BLSP, using the ultimate capitalist symbol of security for political tool has become an upward curve that hasn’t peaked yet. So this version of auto history will stand as an example of the power of message through an engine-propelled hunk of metal.

I spent a good bit of time watching TV and playing in the woods as a kid. There wasn’t much else to do. Knowing that SC started the American Civil War, and remembering the end of Vietnam, I gravitated to history and the stories that the elders around me told. Many of those stories revolved around romanticizing cars. My dad came out of the 1950s generation and told many tales of drag races, bootlegging, drive-ins, wrecks, car dates, and ambulance calls.

My grandmother, born in 1903, remembered her first car ride in Rutherfordton, NC. She had a heart condition so never drove, but her first, 1910s ride was freedom symbolized. She called it a horseless carriage, and remembered it not having a roof or doors. As a teenager, my grandmother was the first generation to experience getting away from the house, the parents, the chores, and the mundane life in the parlor. Her first ride actually ended up stuck in the mud, but the fellow was nice and pushed the car out as she sat in the passenger seat.

On the way to my middle school, the General Lee sat parked on the side of the road. For those who don’t know, the General Lee was the painted Dodge Charger from the TV show “The Dukes of Hazzard.” Having one in North Greenville County, and seeing it on the road and in parades, made the TV show feel more real. I never got tired of seeing it on the bus-ride home, and still remember being sad when it disappeared.

My best friend Mark’s dad had several antique cars, and drove us around Greenville County in them for many years. He had an old Ford truck, a Buick convertible, and a 1930s Ford, complete with rumble seat. Mark ended up driving an old, cherry-apple red Ford Fairlane through high school, and became an artist by drawing tricked-out hot rods.

My other best friend, Russell’s (yes, we were both Russell) dad drove a beat up Chevy Chevette that had Clemson Tigers, a local university football team, stickers all over it. It’s horn played the Clemson fight song and a few cheers. Russell himself ended up driving a beat-up Jeep in high school. The paint job resembled Eddie Van Halen’s guitar and was the first real art car I ever saw.

Around the late 1980s, I read Tom Wolfe’s “Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.” Written in 1968, Wolfe skillfully captures the moment when middle-class kids became hippies. Most notably, he followed the Merry Pranksters on a bus ride across the USA en route to a Beatles concert. The bus, Furthur, was most likely the first ever art car, and it rankled a few coat-tails along it route from San Francisco to New York City. Soon after reading this book, I began to attend concerts where modified buses were present, and the Prankster mentality continued.

As the 1990s began, I got my first glimpse of how an auto can be a marketing tool. Through uncritical eyes, I saw the Oscar Meyer Wienermobile for the first time in Atlanta. A new McDonald’s opened up in my neighborhood and was giving away free burgers and shakes on it’s first open Saturday. True to car-culture nostalgia, this McDonald’s had a 1950s diner theme. So, being poor, I took the free food along with the free entertainment – an Elvis impersonator. As Elvis hammed it up, the Wiener-mobile drove by a few times along the road behind the stage. I’ll never forget it because I got a good laugh out of that surreal, strategic marketing moment.

The second art car I saw was another car that Russell drove. Once out of college, I ended up back in Greenville. Though it was 1995, and the internet was available, not much had changed in my home county. As an adult, the options of things to do revolved around booze, TV, and movies. Russell, being infinitely creative, created a black-light basement of his house and then ventured on to create an art car out of his ride. His car had: toys glued on the dash, anything that looked like a face was a face, toys on the exterior, muppet fur glued all over, and a crazy paint job. People gave him toys, kids would almost jump out of windows as it drove by, and once the engine blew, the junkyard displayed it for a while before demolishing it.

Around this time in my life, I was planning on moving West. Via a new, unique web portal named AOL, I found an alternative culture that I didn’t know existed – Survival Research Labs and Art Cars being the main hits. Art cars in Austin and San Francisco?! Who would’ve thought that there was a community tricking out their rides to the point of creative insanity. Arriving at San Francisco in 1997, I caught my first ever Art Car Convention at SOMART, and was thoroughly amazed at the creativity.

This amazement continued when I ventured to my first Burningman in 1999. How could there be so many people who had tricked out cars, some of which weren’t legally roadworthy? There were even tricked out go-carts, and other mobiles. Burningman even had a bureaucracy that regulated the art cars on the Playa – the Department of Mutant Vehicles. And by then, in San Francisco, an art car caravan met annually and drove across the Golden Gate Bridge as a spectacle to behold. The annual “How Berkeley Can You Be” parade also became an art car magnet.

In 2003, a tipping point occurred in art car history when Matt Gonazlez ran against Gavin Newsom in the mayoral run-off. Usually apolitical burners organized behind the Green Party candidate, and with them came the art cars. At one point in the campaign, a double decker bus, a green fire truck, the famous Mexican Bus, and several other art cars drove around The City campaigning for Matt. I personally tried to organize an art car caravan one Saturday and only had two cars show up. Still, the presence of the alternative art cars marked a new stage in the potential of co-opting a symbol of the American Dream.

From my experience, this is when the concept of combining the ultimate American icon into a political tool began to take shape. On a raw, no-budget, grass roots level, activists began taking the romanticism of the mobile machine and turning it into a political marketing tool. After my meager Art Cars for Matt Caravan, I felt that the potential had yet to be realized.

As my anecdotal history began to point to the potential of art car activism, Ben Cohen and BLSP began their own, bigger-budget art car revolution in Iowa. Cohen, co-founder of Ben & Jerry’s Ice Cream, was no stranger to the symbolic power of the auto. He and Jerry had two CowMoblies that they had personally taken on the road to scoop out their ice cream. Cohen’s first political art car idea was Mable the Bus for the “Move Our Money” campaign in Iowa. Shrinkwrapped in money, Mable went on tour with 10 inflatables, and a Vaudeville stage featuring Uncle Sam and his Two Muses.

In 2002, Cohen upped the spectacle via six modified vehicles that went on the road for a short-lived True Majority Festival. Along with 10 carnival booths, 13 tour people, a 26-foot Ryder truck, and 3 full-time bookers, the “educational vehicles” consisted of: a yellow, double-decker schoolbus, an RV as a bar chart, a natural-gas-fueld vehicle as a tree, and the wildly popular PiggieMobile. Out of everything, they learned that the Piggies were the draw, so they scrapped the rest and kept the Piggies on the road.

Continuing this critical mass, an alternative fuel movement began to spread across the USA. In 2004, several SVO and biodiesel buses began to tour the country and Central America. SVO, straight veggie oil, vehicles suck veggie oil out of the backs of restaurants and filter it to burn as free fuel. The band Aphrodesia and the Big Tadoo Puppet Crew toured separately across the country on veggie oil while the Sustainable Solutions Caravan drove to Costa Rica. Other groups converted buses and did similar tours. Though not art cars, the fact that the engines were experimental systems frames the same concept. The alt-fuel movement added another spoke to the wheel of changing the auto paradigm into a political educational tool.

After their success with the Pants On Fire and Spanky cars, both of which criticized George Bush, Cohen’s BLSP put the OreoMoble on the road in 2005. With a budget to make educational vehicles a strategic marketing tool for positive change, BLSP based this newest ride on the now famous “Oreo Cartoon.” A Flash animation, the “Oreo Cartoon” broke the federal budget down via cookies, with Ben Cohen as the host. Simplifying the budget allowed Americans to see that our tax dollars didn’t go where we wanted it to. The OreoMobile, a van pulling a trailer, demonstrated this via huge Oreo cookies.

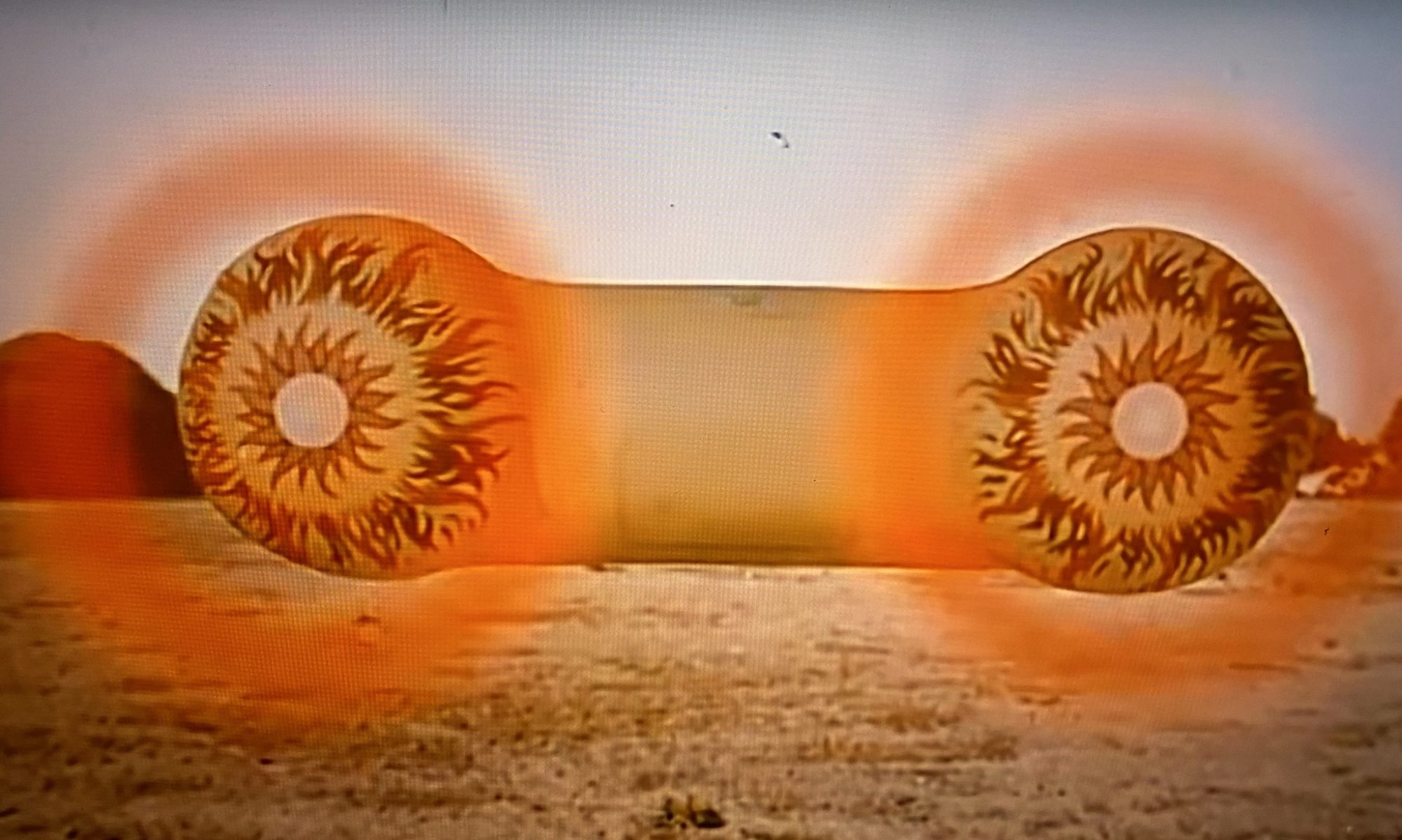

The educational vehicle’s power rose to another level in 2006. Along with the Piggies, still on the road and wildly successful, and the OreoMobile, BLSP has introduced the CarnyMobile and the PieMobiles. Continuing their goal of educating Americans about the federal budget, the CarnyMobile does this via two carnival games. One of those games, the high striker, transforms into a trailer that flies two mobile billboards. The PieMobiles, two Honda Elements, stand as 10-feet-tall pie charts of the federal budget. In Iowa and New Hampshire, they add to the evolving fleet of educational vehicles.

In summary, educational vehicles have usually been RVs that you tour through, or mobile libraries that haul books. Never before, and to such an extent, has the concept of a modified vehicle been combined with a political message and a marketing strategy. Using the meme of the automobile as a gateway to freedom, individuality, and the achievement of the “american dream,” art car activism, via modified educational vehicles, has entered a new phase in America’s over-advertised landscape. Along with the continuing alt-fuels movement, new strategies will evolve to hopefully break into the mind of the over-consumed citizen. Though the fun and imaginative side of the culture will continue to exist, and hot rods and low riders will still be created, a new model has created a potential to reframe the growing debates that vex our society.